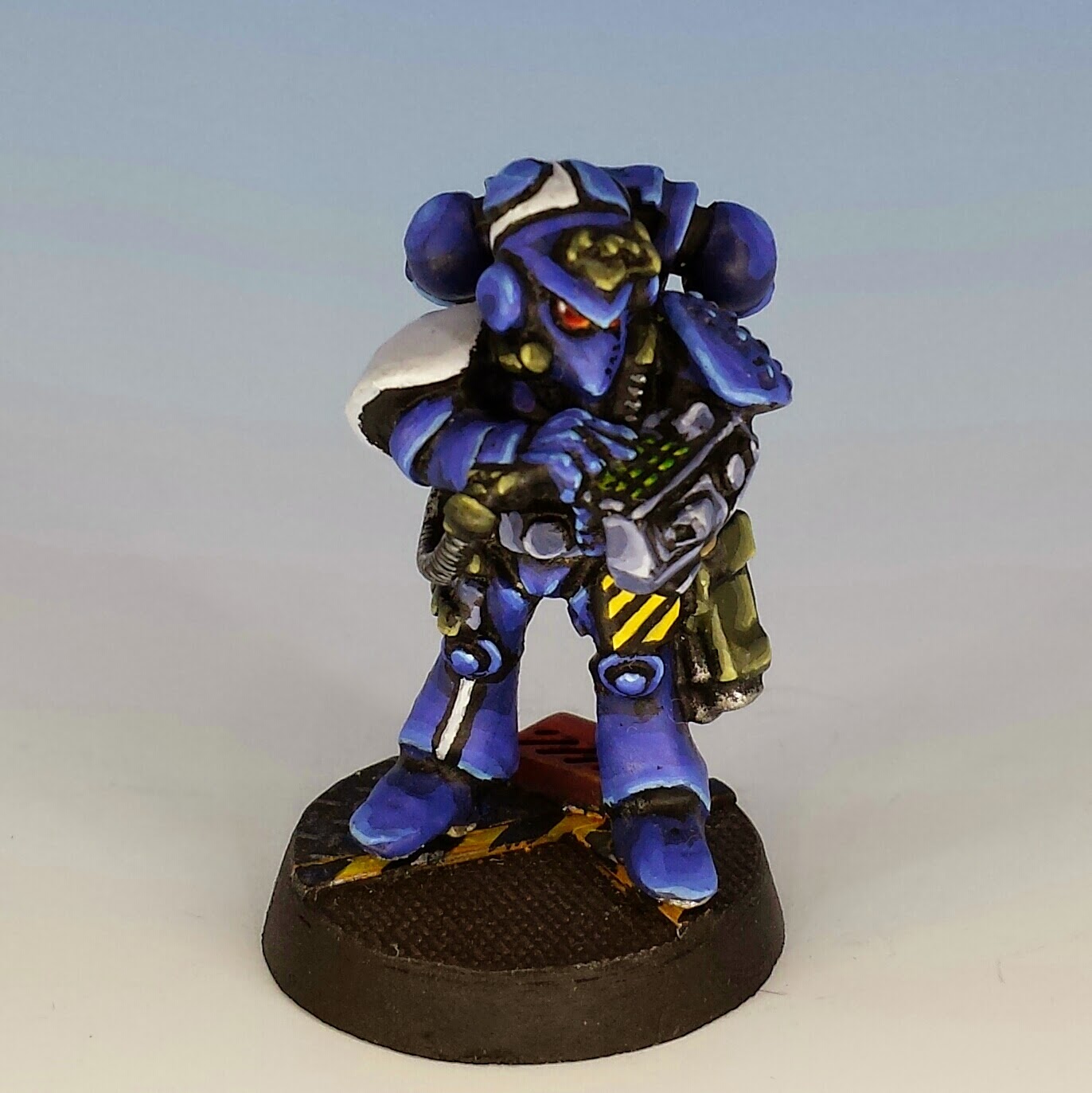

Welcome to my website, showcasing my collection of classic Citadel miniatures from the 1980's, also known as Oldenhammer miniatures.

![]() In the mid-1980's, a unique genius descended upon Citadel Miniatures and its parent, Games Workshop. It started with GW's visionary founders, Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson. Subsequently, under the leadership of the mephistophelean Bryan Ansell, this collective inspiration intensified. A dog's breakfast of punks, hippies and hobbyists came together to transform Citadel into the closest thing that the gaming world has to Athens in the age of Pericles.

In the mid-1980's, a unique genius descended upon Citadel Miniatures and its parent, Games Workshop. It started with GW's visionary founders, Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson. Subsequently, under the leadership of the mephistophelean Bryan Ansell, this collective inspiration intensified. A dog's breakfast of punks, hippies and hobbyists came together to transform Citadel into the closest thing that the gaming world has to Athens in the age of Pericles.

There were artists like John Blanche and Gary Chalk, who brought the vision of Bruegel the Elder or Albrecht Durer to the gaming table. At the same time, a cohort of precocious sculptors advanced the art of miniature sculpting by leagues in just a few short years. Kevin Adams, Bob Olley, Nick Bibby, Alan Perry, Michael Perry, Aly Morrison, Trish Morrison, and Jes Goodwin not only made remarkable technical progress, but they all found ways of expressing their own unique aesthetic on a canvass of lead only 25mm high. Then there were the talented and twisted game designers, like Rick Priestly, Jervis Johnson and Graeme Davis, who wove this visual style into a multiverse which was at once so chaotic and yet so unified in its tone of adventure and insolence.

(And there was also Sabbat.)

For my own part, I love the miniatures that come from Citadel's classic period because of their baroque exuberance. They are miniatures as designed by Rembrandt, if Rembrandt illustrated Fighting Fantasy books. These minis are not overly realistic (like many contemporary miniatures from historical ranges). Instead, classic Citadel sculpts enhance the size of faces, hands and feet so that the personality of each figure can take the foreground. At the same time, these miniatures don't adopt the overly "heroic" style of later Warhammer figures (1990 to the present), in which weapons, armour and gear are exaggerated in size and ornament, making the miniatures appear more like anime robots than people.

![]() Oldenhammer miniatures are about drama. And no range of Citadel miniatures captures this drama in more colour than the Talisman range. Talisman, of course, is the fantasy board game with almost as many lives as a cat. Gary Chalk inked the artwork in the original set, and the Citadel sculptor of the Talisman miniatures perfectly captured Mr. Chalk's style: an etched quality with lots of character, and a whiff of John Tenniel's famous illustrations of Alice in Wonderland. The Wonderland connection is even apparent in the hearts/spades motif in some of his pictures.

Oldenhammer miniatures are about drama. And no range of Citadel miniatures captures this drama in more colour than the Talisman range. Talisman, of course, is the fantasy board game with almost as many lives as a cat. Gary Chalk inked the artwork in the original set, and the Citadel sculptor of the Talisman miniatures perfectly captured Mr. Chalk's style: an etched quality with lots of character, and a whiff of John Tenniel's famous illustrations of Alice in Wonderland. The Wonderland connection is even apparent in the hearts/spades motif in some of his pictures.

Here is the first installment of my version of these great miniatures:

If anyone can tell me which sculptor is responsible for these miniatures, I'd be very much obliged.

In the mid-1980's, a unique genius descended upon Citadel Miniatures and its parent, Games Workshop. It started with GW's visionary founders, Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson. Subsequently, under the leadership of the mephistophelean Bryan Ansell, this collective inspiration intensified. A dog's breakfast of punks, hippies and hobbyists came together to transform Citadel into the closest thing that the gaming world has to Athens in the age of Pericles.

In the mid-1980's, a unique genius descended upon Citadel Miniatures and its parent, Games Workshop. It started with GW's visionary founders, Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson. Subsequently, under the leadership of the mephistophelean Bryan Ansell, this collective inspiration intensified. A dog's breakfast of punks, hippies and hobbyists came together to transform Citadel into the closest thing that the gaming world has to Athens in the age of Pericles.There were artists like John Blanche and Gary Chalk, who brought the vision of Bruegel the Elder or Albrecht Durer to the gaming table. At the same time, a cohort of precocious sculptors advanced the art of miniature sculpting by leagues in just a few short years. Kevin Adams, Bob Olley, Nick Bibby, Alan Perry, Michael Perry, Aly Morrison, Trish Morrison, and Jes Goodwin not only made remarkable technical progress, but they all found ways of expressing their own unique aesthetic on a canvass of lead only 25mm high. Then there were the talented and twisted game designers, like Rick Priestly, Jervis Johnson and Graeme Davis, who wove this visual style into a multiverse which was at once so chaotic and yet so unified in its tone of adventure and insolence.

(And there was also Sabbat.)

For my own part, I love the miniatures that come from Citadel's classic period because of their baroque exuberance. They are miniatures as designed by Rembrandt, if Rembrandt illustrated Fighting Fantasy books. These minis are not overly realistic (like many contemporary miniatures from historical ranges). Instead, classic Citadel sculpts enhance the size of faces, hands and feet so that the personality of each figure can take the foreground. At the same time, these miniatures don't adopt the overly "heroic" style of later Warhammer figures (1990 to the present), in which weapons, armour and gear are exaggerated in size and ornament, making the miniatures appear more like anime robots than people.

Oldenhammer miniatures are about drama. And no range of Citadel miniatures captures this drama in more colour than the Talisman range. Talisman, of course, is the fantasy board game with almost as many lives as a cat. Gary Chalk inked the artwork in the original set, and the Citadel sculptor of the Talisman miniatures perfectly captured Mr. Chalk's style: an etched quality with lots of character, and a whiff of John Tenniel's famous illustrations of Alice in Wonderland. The Wonderland connection is even apparent in the hearts/spades motif in some of his pictures.

Oldenhammer miniatures are about drama. And no range of Citadel miniatures captures this drama in more colour than the Talisman range. Talisman, of course, is the fantasy board game with almost as many lives as a cat. Gary Chalk inked the artwork in the original set, and the Citadel sculptor of the Talisman miniatures perfectly captured Mr. Chalk's style: an etched quality with lots of character, and a whiff of John Tenniel's famous illustrations of Alice in Wonderland. The Wonderland connection is even apparent in the hearts/spades motif in some of his pictures.Here is the first installment of my version of these great miniatures:

Druid, Monk (with bloodied mace) and Priest (with boring sermon).

Prophetess, Sorceress and Wizard.

Minstrel, Elf and Dwarf

Toad (modern version), Troll and Warrior

Thief, Assassin and Ghoul

If anyone can tell me which sculptor is responsible for these miniatures, I'd be very much obliged.